The Beginner's Guide

"The Beginner's Guide"

I really like Davey Wreden’s work, and I wrote “The Stanley Parable: A Carnival of Anti-design and Fantastic Philosophy” seven months ago. But after some time, I did not try his second game “The Beginner’s Guide” or even write a review, because I knew it would be a game that is hard to comment.

After William Pugh, the co-developer of The Stanley Parable, left the studio, the sense of humor in the studio seemed vanished with him, leaving The Beginner’s Guide fulfilled with Davey Wreden’s dull, repetitive, obscure and heavy emotion.

“The Game Without Player”

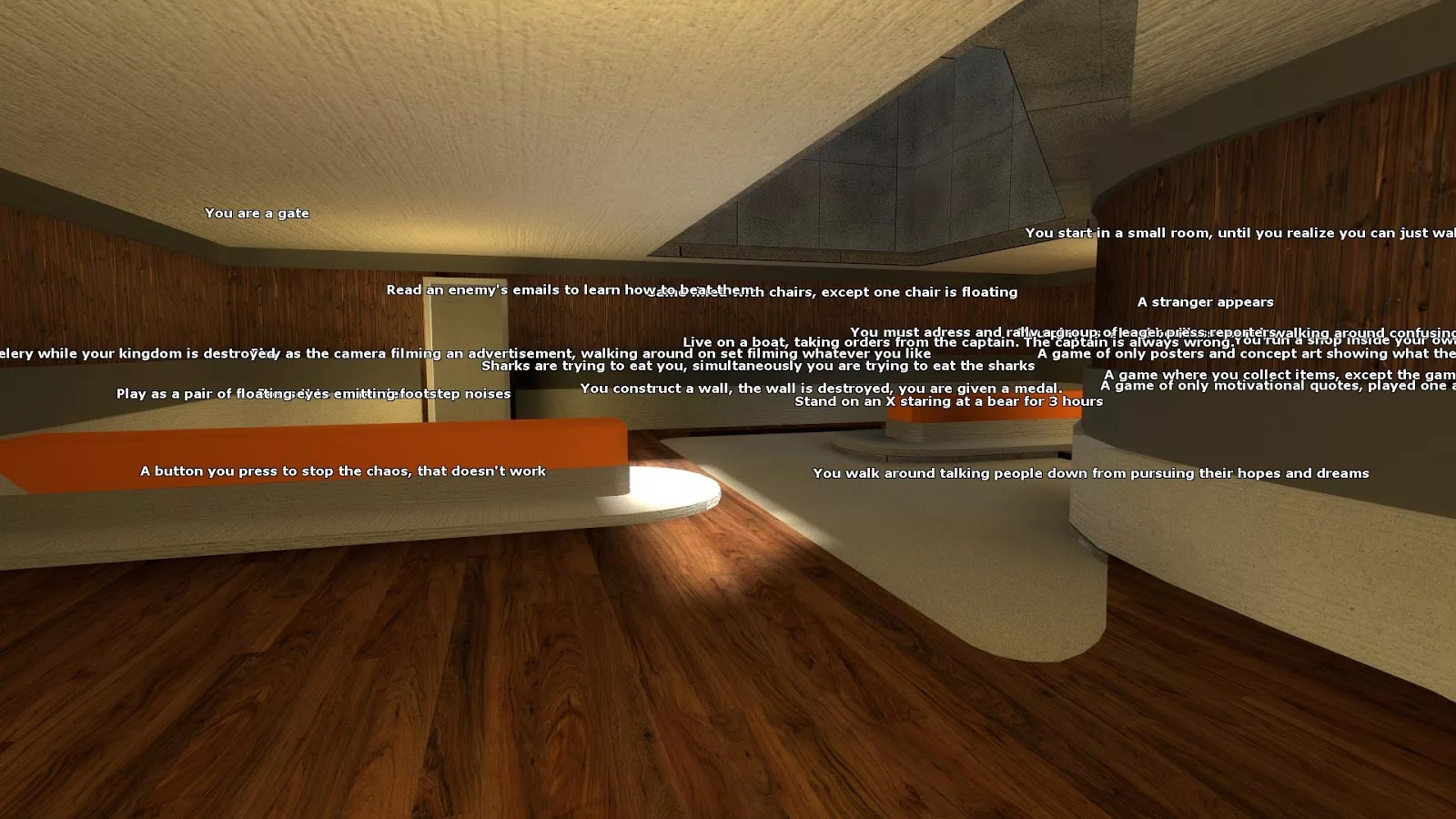

“The Beginner’s Guide” does not deconstruct the play element in the game because many kinds of “simulation games” have already done that. Instead, “The Beginner’s Guide” tries to catch the existence of “Player,” and the idea of anti-participation or the bigotry “Coda” expressed in the game.

So let’s start with Coda’s games.

Please think about a question first: Could games ever be “unplayful”? And can games have no players?

In every game design book, all seasoned designers are trying to tell you - “You should let “players” playtest your games, and improve the game with feedbacks continuously,” or “make games players love,” or “we should follow “Player-Centric Design” and making players interested in our games is our priority,” etc. This is also an inner paradox for media expressing themselves when thinking about “games as art” as a game designer. Although Rembrandt’s “De Nachtwacht” is a product of a commercial order, thinking with the logic of modern art: “art is an expression and exaggeration of ego, so why should I care about players during the design process?”

“No art is meant to entertain others.” Why should games have to be “playful”?

When games are transforming from an entertaining object into a way to build experience with the multimedia technology, they closely connect with modern art. And Coda’s game follows the logic of modern art, when his experience constructed may be more impressive and private than the installation art in modern art museums, because it should not be “view-only,” but with participation (there have been many attempts such as “The Static Speaks My Name,” “Gone in November,” and “Tale of Tales”)

“Playful” and “entertaining,” are like the perspective rule which has been limiting modern drawing for hundreds of years or the traditional Christian aesthetic standard, “is not or no longer the things that are inseparable in us.”

Coda’s work is not only “unjoyful,” but “unplayable.”

Coda’s work is closed. Programming has already locked in the rules. It is like a safe with designer’s notes inside, and shall never be opened again. During the production, Coda put his conversation with his ego, his loneliness, his craziness and fanatics behind the door you will never trespass. These are the “invisible things in work”, just like Picasso’s drafts before his final painting. They are work with solid content, but meant to be replaced. Or, they are never meant to be shown. What if the game only shows the players little part of the whole? You can never ask games to show you all the content, just like you can never totally figure out Shakespeare’s literature, or the meaning of this real world.

Robert McKee mentioned writers in the twentieth centuries, such as Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, and Samuel Beckett, who all emphasize the importance of “cutting the connections between artists and the outside reality, to further cut down the connection between artists and the majority of audiences.” He reasoned Dadaism, Stream of Consciousness, Theatre of the Absurd and more as “a conceal of the artists’ private world; and the entrance of this world is controlled by the artists.”

Coda stands on the top of his work, watches the players indifferently like a cold sculpture. Players are not guests who need to be entertained and ingratiated, but passengers outside the show windows who would pass quickly and can only take a glance inside then leave. He inverts the relationship between players and designers in modern game design methodology. He is like Nietzsche who reevaluate everything. Coda is not a designer. Coda is God.

“A God Who Dies” ——- Coda is not only the God for games. He is a God for himself. He makes games for himself.

When one moves his motivation of making games from pleasing players to pleasing himself, his games are no longer games, but a diary he writes to himself just for locking down his memory. When he leaves his thoughts behind the door that will never open, he burns his memory to leave them in the past forever and hopes will never remember.

Coda’s presentation on his work is not only his portfolio but his growing memory, his notebook. The door puzzle which shows up many times, forms an organized factor in his games, just as himself saying goodbye to the past over and over again. Only forgetting the past during the struggling present, can make him to the future. 已往之不谏,来者之可追(A Chinese poetic way to express the meaning of last sentence).

That reminds me of a theory of Micro Game shared by someone in AMAZE Indie Game Festival:

“Game production can be a way to try out and practice your design theory, or a way to your self-catharsis, or self-care, or your therapy, or your life snapshot, or even a way to communicate.”

“When Games become the real ‘art,’ its purpose directs to the producer himself.”

Charles Baudelaire thinks modern people can only use ascetic practices to make their own body, behaviors, feelings, emotions, even his existence, to be art. In his opinion, people as modern citizens should not explore themselves, looking for their mysteries or hidden truth, but “creating themselves.” The modernization of art does not make people free themselves in their existences but force them to face the task, which is, to build themselves.

When making games becomes a lifestyle and game texts become one’s diary, players then can only be the friends who would never understand each other. The rules set the comfort zone of the producers, limiting those emotions that they don’t want, and are not willing to share. Just as everyone who walks is lonely, his inner tiding emotions and thoughts are not for sharing. Because if they do so, they can be as ludicrous as putting themselves into a zoo, letting others watch and comment publicly.

“The Arrogator” ——- So the narrator in the game “Davey Wreden” is not only a peeper, but an arrogator.

In the process of presentation, to facilitate players’s move, the protagonist “Davey Wreden” helps us a lot in exploring it. He helps us to modify Coda’s games, to make them “playable.” He makes the walls transparent to show us the hidden items, enter some rooms that are meant to be locked or open the jail that is supposed to be opened in one hour, and solves the puzzle which should take you one hour to think about - you can know the result instantly, instead of suffering from those tedious process.

At the end of the game, we even know he has modified the content, for example, adding light towers to emphasize the game’s meanings, organizing the work into chapters to show closer bonds between each of Coda’s work, improving the credibility of his words commenting on Coda’s work. If the producer Devid Wreden (himself, not the narrator) has made a game using only single piece of Coda’s work, it would be a very impressive User-Experience project, such as “stay in jail for one hour,” or “flying thoughts behind the door you can never open.”

But the most impressive resolution is:

Davey Wreden did not show his work using the logic of artwork. He connects these work by creating a narrator “Davey Wreden” who tries to interpret Coda’s work. The interpretation not only shows his thoughts and creativity in a low tier but also shows high-tier prudence by using interactions between the narrator, the arrogator and the game itself. And the thing makes the whole mechanics perfect is: the arrogator he creates, is “David Wreden”, himself.

He even gives a real email address in the game.

As a game which shows its “meta” element since the first voiceline, it easily confused the players using complex multilayer structure in meta-texts (the narrator’s lines), and implants the question of “Is the narrator misinterpreting these games?” into players’ mind after “tricking” players about commenting on the work. That is important.

Just like you who sit in front of the screen and read this article, you may say “oh so that’s what it is” after reading and close this web tab with satisfaction. But the way how texts can be understood is open. Neither you nor I, nor the writer has the absolute right to explain the work. We can only explain those “maybe” but not “it has to be.”

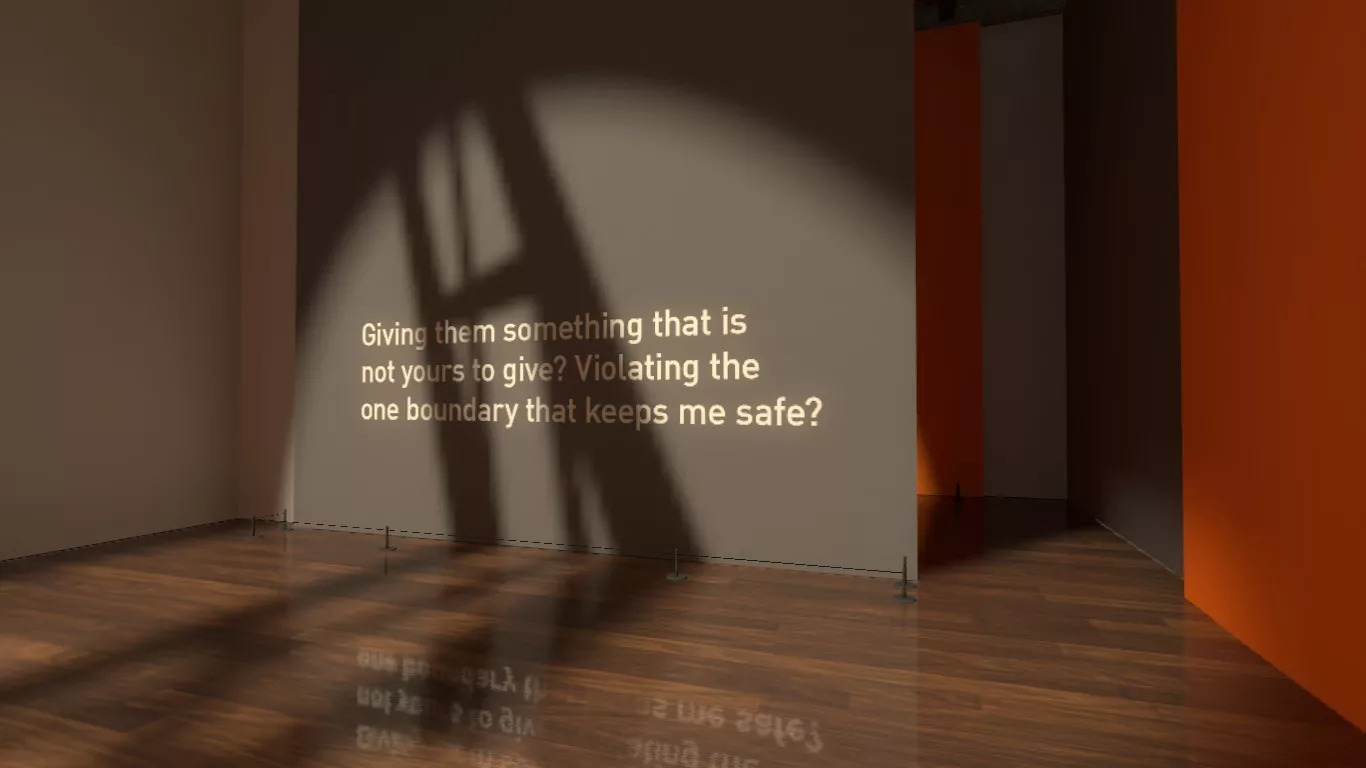

The sin of the narrator “Davey Wreden” is not his endeavor to interpret Coda’s work, but trying to replace every possibility with his absolute explanation. When he tries to characterize Coda to be “a Coda who is desirous of others’ understanding” even by modifying the game code to form a harmony between his interpretation and the work, he arrogates.

Understanding the producer by his work is the way of interpretation “Davey Wreden” (the narrator) tries to mislead us to. But it is also the way David Wreden tries to eliminate. That is the way which shatters the relationship between producers and their work. Interpreters look through the pinhole of games, states their definite explanation of games and the producers, and leaves no rest space but desperation to designers.

The end of interpretation should be the work. Not the producer.

Is Coda, the creator of all those games, even similar to the words “Davey Wreden” said? Does he really need others’ understanding, comments, or compliments? The compliments towards Davey Wreden’s interpretation makes Davey feels good, but what do those compliments and “understanding” mean to Coda?

The man who stands behind The Beginner’s Guide is the real David Wreden, the narrator “Davey Wreden,” and also the producer Coda. He is the narrator who creates The Stanley Parable. He smiles with his faint heart and his pain. His emotions and values are built based on others’ compliments.

He may want to cut the unbilical cord connecting him with his past, just like the door you must close before moving on; He may want to put down his burden, his fragile proud based on others’ comments. Those things may be the load which drags him from the future, or from himself. It cuts his putrid body like a scalpel, force him saying goodbye to his past.

He may want to be Coda, the man who has his admiration, the man who lives in his past and future.

Appendix I ——- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4N6y6LEwsKc

Appendix II ——-

After the release of The Stanley Parable, Davey Wreden underwent a dramatic change in mind. He published these article when he got an award on 2013.

So I finished the comic, and read back over it, and thought to myself “There’s no way I can post this online.” The point of the comic was purely just to clarify that financial and critical success does not simply make your insecurities go away. “If you were insecure about other peoples’ opinions of you and addicted to praise in order to feel good about yourself, the dirty truth is that there is no amount of praise you can receive that will make that insecurity goes away. What fire dies when you feed it?” But if I go posting on the internet about how awful I felt receiving all these Game of the Year awards, no one is going to take that seriously. “Oh, yeah, we get it, real rough life you’ve got there. Sounds pretty miserable to be loved for your art. Maybe go cry about it into a pile of money?” And then of course I’m back in the problem I was trying so hard to avoid in the first place, where I’m stressing out about peoples’ opinions of me and forgetting simply to feel good about myself. I want to be able to like myself and my work, but it becomes SIGNIFICANTLY harder once people on the internet start asking you to feel ashamed of yourself. It’s really really hard to ignore. So either I share this thing that is simply True, that is a representation of what I actually felt at this time, and risk being shamed for it, or I hide it away and continue to pretend that success means you never feel shitty about anything ever again in your life. I’m going to post it here, but I also decided to write this preamble to contextualize it. If you do decide to read the comic, all I can ask is that you enter into it open-mindedly. You may not agree with or understand my feelings, but I guarantee you they are True, they are what I felt at that time. If you’ve read this and still think to yourself “oh come on, this guy can’t be serious, there’s no way that receiving game of the year awards would cause anyone to feel upset,” then I’d perhaps tell you that it’s unlikely that the rest of this post will convince you, and maybe now would be a good time to stop reading? Obviously you get to do whatever you want, that’s how this creator/audience thing works, and no matter what happens I’ll be fine. But I want to stress that the weight I have carried is real and it is heavy. And despite my trepidation about posting this online, I really do want to share it with you. I want to be able to show you this weight, to put you in my head. I am compelled to. It is just in my blood. I have no other explanation. Thank you for joining me.

“Game of the Year” ——- Basically here’s what happened: after the launch of Stanley Parable, I became a bit depressed. Largely this is because in those months, SO much attention was directed at the game and at me personally. And while I could not even begin to put into words how utterly grateful and astonished and humbled I am by the enormous response to Stanley Parable (all of you are the reason I can now devote my life to this kind of work), those months after launch were intensely intensely stressful. People don’t just play your game and then shut up, they’ll come back to you in force and really let you know how it made them feel. The vast majority of the response to Stanley was extremely positive, some of it was also extremely negative. I had emails from people who told me I had forever changed the way they saw the world, emails from people who wanted me to know I was a spineless coward who should hate himself, emails from people asking for advice and for tech support and to look at their work and just talk about what they’d been up to, emails from fans and journalists asking over and over and over and over and over where the idea for the game came from, until the answers to those questions simply became stock and lost their meaning and even I began to lose track of where the idea had actually come from. Thousands of people asking you to carry some amount of weight for them, to hear them, to talk to them, to tell them that things are going to be okay, to not turn them away. I tried, I did the best I knew how to do, but after a certain point the many little requests added up and their collective weight broke my back. I couldn’t do it any more. I couldn’t talk to more people. I couldn’t continue to use other peoples’ opinions of myself to feel good about myself and about my work. Every time I turned to someone else’s opinion of the game, I felt less sure of my own opinion of it. I began to forget why I liked the game. I was losing the thing I had created. So I withdrew. I basically checked out of the world, told people “I’m just gonna be by myself for a while.” I had never done that before. I spent a few months not really talking to anyone. It was lonely, but it was nice. Then toward the end of 2013, news outlets begin releasing their Game of the Year awards, and Stanley Parable is back in the spotlight. Suddenly the personal requests start flooding back in again. Suddenly I am the object of peoples’ emotional baggage again. The GotY awards did not cause me to be depressed, they simply unearthed a depression I had been harboring and trying to bury since the launch of the game. But for whatever inexplicable reason, I felt depressed and anxious again. (part of what made the depression worse was that being given awards actually did not help me feel any better. “Is something wrong with me??” one tends to ask in a situation like this) So: to help myself better understand and isolate the feeling of depression around the GotY awards, I wrote and drew a comic to explain what I had been feeling. It was simply the best expression I had for the thoughts and emotions that were running through my head at the time at the time, I just wanted to put it into some words to help make it less nebulous and unknowable. I wanted something I could hold in front of myself and say “This. This is what I am experiencing.” It’s nice to get it out of your head.

If you try to understand, this might be the best beginner’s guide ever. A best, sincere gift from an artist who goes through such vicissitude.